Tuesday, September 9, 2014

Sunday, August 31, 2014

USS Essex

USS Essex (CV/CVA/CVS-9) was an aircraft carrier, the lead ship of the 24-ship Essex class built for the United States Navy during World War II. She was the fourth US Navy ship to bear the name. Commissioned in December 1942, Essex participated in several campaigns in the Pacific Theater of Operations, earning the Presidential Unit Citation and 13 battle stars. Decommissioned shortly after the end of the war, she was modernized and recommissioned in the early 1950s as an attack carrier (CVA), and then eventually became an antisubmarine aircraft carrier (CVS). In her second career she served mainly in the Atlantic, playing a role in the Cuban missile crisis. She also participated in the Korean War, earning four battle stars and the Navy Unit Commendation. She was the primary recovery carrier for the Apollo 7 space mission.

She was decommissioned for the last time in 1969 and sold for scrap in 1975.

Pilots briefed before raid on Formosa

Following her builders trials and shakedown cruise (both also accelerated), Essex steamed to the Pacific in May 1943 to begin a succession of victories which would bring her to Tokyo Bay. Departing from Pearl Harbor, she participated with Task Force 16 (TF 16) in carrier operations against Marcus Island (31 August 1943); was designated the flagship of TF 14 and struck Wake Island (5–6 October); participated in carrier operations during the Rabaul strike (11 November 1943), along with Bunker Hill and Princeton; launched an attack with Task Group 50.3 (TG 50.3) against the Gilbert Islands where she also took part in her first amphibious assault, the landing on Tarawa Atoll (18–23 November). Refueling at sea, she cruised as flagship of TG 50.3 to attack Kwajalein (4 December). Her second amphibious assault delivered in company with TG 58.2 was against the Marshall Islands (29 January–2 February 1944).

Pilots briefed before raid on Formosa

Following her builders trials and shakedown cruise (both also accelerated), Essex steamed to the Pacific in May 1943 to begin a succession of victories which would bring her to Tokyo Bay. Departing from Pearl Harbor, she participated with Task Force 16 (TF 16) in carrier operations against Marcus Island (31 August 1943); was designated the flagship of TF 14 and struck Wake Island (5–6 October); participated in carrier operations during the Rabaul strike (11 November 1943), along with Bunker Hill and Princeton; launched an attack with Task Group 50.3 (TG 50.3) against the Gilbert Islands where she also took part in her first amphibious assault, the landing on Tarawa Atoll (18–23 November). Refueling at sea, she cruised as flagship of TG 50.3 to attack Kwajalein (4 December). Her second amphibious assault delivered in company with TG 58.2 was against the Marshall Islands (29 January–2 February 1944).

Essex — in TG 58.2 – now joined with TG 58.1 and TG 58.3 to constitute Task Force 58 (the "Fast Carrier Task Force"), to launch an attack against Truk (17–18 February) during which eight Japanese ships were sunk. En route to the Mariana Islands to sever Japanese supply lines, the carrier force was detected and received a prolonged aerial attack which it repelled in a businesslike manner and then continued with the scheduled attack upon Saipan, Tinian and Guam (23 February).

After this operation, Essex proceeded to San Francisco for her single wartime overhaul. Following her overhaul, Essex became the carrier for Air Group 15, the "Fabled Fifteen," commanded by the U.S. Navy's top ace of the war, David McCampbell. She then joined carriers Wasp and San Jacinto in TG 12.1 to strike Marcus Island (19–20 May) and Wake (23 May). She deployed with TF 58 to support the occupation of the Marianas (12 June – 10 August); sortied with TG 38.3 to lead an attack against the Palau Islands (6–8 September), and Mindanao (9–10 September) with enemy shipping as the main target, and remained in the area to support landings on Peleliu. On 2 October, she weathered a typhoon and four days later departed with Task Force 38 (TF 38) for the Ryukyus. (TF 38 was actually the same formation as TF 58, the nomenclature being changed to reflect the rotation of command staffs employed by the Navy for efficiency in executing multiple operations; this rotation allowed constant front-line deployment of the ships and their crews while providing operational planning time at better-equipped, rear-area base facilities for the command structure not currently afloat).

For the remainder of 1944, she continued her frontline action, participating in strikes against Okinawa (10 October), and Formosa (12–14 October), covering the Leyte landings, taking part in the Battle for Leyte Gulf (24–25 October), and continuing the search for enemy fleet units until 30 October, when she returned to Ulithi, Caroline Islands, for replenishment. She resumed the offensive and delivered attacks on Manila and the northern Philippine Islands during November. On 25 November, for the first time in her far-ranging operations and destruction to the enemy, Essex received damage. A kamikaze hit the port edge of her flight deck landing among planes gassed for takeoff, causing extensive damage, killing 15, and wounding 44.

Lieutenant Yamaguchi's Yokosuka D4Y3 (Type 33) Suisei diving at Essex, 25 November 1944. The dive brakes are extended and the non-self-sealing port wing tank is trailing fuel vapor and/or smoke.

Lieutenant Yamaguchi's Yokosuka D4Y3 (Type 33) Suisei diving at Essex, 25 November 1944. The dive brakes are extended and the non-self-sealing port wing tank is trailing fuel vapor and/or smoke.

A Japanese kamikaze aircraft explodes after crashing into Essex’s flight deck amidships. 25 November 1944

Following quick repairs, she operated with the task force off Leyte supporting the occupation of Mindoro

(14–16 December). She rode out the typhoon of 18 December and made

special search for survivors afterwards. With TG 38.3, she participated

in the Lingayen Gulf operations, launched strikes against Formosa, Sakishima, Okinawa, and Luzon. Entering the South China Sea in search of enemy surface forces, the task force pounded shipping and conducted strikes on Formosa, the China coast, Hainan, and Hong Kong. Essex withstood the onslaught of the third typhoon in four months (20–21 January 1945) before striking again at Formosa, Miyako-jima and Okinawa (26 – 27 January).

A Japanese kamikaze aircraft explodes after crashing into Essex’s flight deck amidships. 25 November 1944

Following quick repairs, she operated with the task force off Leyte supporting the occupation of Mindoro

(14–16 December). She rode out the typhoon of 18 December and made

special search for survivors afterwards. With TG 38.3, she participated

in the Lingayen Gulf operations, launched strikes against Formosa, Sakishima, Okinawa, and Luzon. Entering the South China Sea in search of enemy surface forces, the task force pounded shipping and conducted strikes on Formosa, the China coast, Hainan, and Hong Kong. Essex withstood the onslaught of the third typhoon in four months (20–21 January 1945) before striking again at Formosa, Miyako-jima and Okinawa (26 – 27 January).

For the remainder of the war, she operated with TF 58, conducting attacks against the Tokyo area (16–17, and 25 February) both to neutralize the enemy's air power before the landings on Iwo Jima and to cripple the aircraft manufacturing industry. She sent support missions against Iwo Jima and neighboring islands, but from 23 March – 28 May was employed primarily to support the conquest of Okinawa.

Essex being modernized, 1949.

In the closing days of the war, Essex took part in the final

telling raids against the Japanese home islands (10 July – 15 August).

Following the surrender, she continued defensive combat air patrols until 3 September, when she was ordered to Bremerton, Washington for inactivation. On 9 January 1947, she was placed out of commission in reserve. Modernization endowed Essex

with a new flight deck, and a streamlined island superstructure on 16

January 1951, when she was recommissioned, with Captain A. W. Wheelock

commanding.

Essex being modernized, 1949.

In the closing days of the war, Essex took part in the final

telling raids against the Japanese home islands (10 July – 15 August).

Following the surrender, she continued defensive combat air patrols until 3 September, when she was ordered to Bremerton, Washington for inactivation. On 9 January 1947, she was placed out of commission in reserve. Modernization endowed Essex

with a new flight deck, and a streamlined island superstructure on 16

January 1951, when she was recommissioned, with Captain A. W. Wheelock

commanding.

Essex after her SCB-27A modernization.

After a brief cruise in Hawaiian waters, she began the first of three tours in Far Eastern waters during the Korean War. She served as flagship for Carrier Division 1 (CarDiv 1) and Task Force 77. She was the first carrier to launch F2H Banshees

on combat missions; on 16 September 1951, one of these planes, damaged

in combat, crashed into aircraft parked on the forward flight deck

causing an explosion and fire which killed seven. After repairs at Yokosuka, she returned to frontline action on 3 October to launch strikes up to the Yalu River and provide close air support for U.N. troops. Her two deployments in the Korean War were from August 1951 – March 1952 and July 1952 – January 1953.

Essex after her SCB-27A modernization.

After a brief cruise in Hawaiian waters, she began the first of three tours in Far Eastern waters during the Korean War. She served as flagship for Carrier Division 1 (CarDiv 1) and Task Force 77. She was the first carrier to launch F2H Banshees

on combat missions; on 16 September 1951, one of these planes, damaged

in combat, crashed into aircraft parked on the forward flight deck

causing an explosion and fire which killed seven. After repairs at Yokosuka, she returned to frontline action on 3 October to launch strikes up to the Yalu River and provide close air support for U.N. troops. Her two deployments in the Korean War were from August 1951 – March 1952 and July 1952 – January 1953.

On 1 December 1953, she started her final tour of the war, sailing in the East China Sea with what official U.S. Navy records describe as the "Peace Patrol". From November 1954 – June 1955, she engaged in training exercises, operated for three months with the United States Seventh Fleet, assisted in the Tachen Islands evacuation, and engaged in air operations and fleet maneuvers off Okinawa.

F4D-1 Skyray approaches Essex during her last cruise as an attack carrier 1959–60.

In the fall of 1957, Essex participated as an anti-submarine carrier in the NATO exercise Strikeback and in February 1958, deployed with the 6th Fleet until May, when she shifted to the eastern Mediterranean. Alerted to the Middle East crisis on 14 July 1958, she sped to support the U.S. Peace Force landing in Beirut, Lebanon,

launching reconnaissance and patrol missions until 20 August. Once

again, she was ordered to proceed to Asian waters, and transited the Suez Canal to arrive in the Taiwan

operational area, where she joined TF 77 in conducting flight

operations before rounding the Horn and proceeding back to Mayport.

F4D-1 Skyray approaches Essex during her last cruise as an attack carrier 1959–60.

In the fall of 1957, Essex participated as an anti-submarine carrier in the NATO exercise Strikeback and in February 1958, deployed with the 6th Fleet until May, when she shifted to the eastern Mediterranean. Alerted to the Middle East crisis on 14 July 1958, she sped to support the U.S. Peace Force landing in Beirut, Lebanon,

launching reconnaissance and patrol missions until 20 August. Once

again, she was ordered to proceed to Asian waters, and transited the Suez Canal to arrive in the Taiwan

operational area, where she joined TF 77 in conducting flight

operations before rounding the Horn and proceeding back to Mayport.

Essex joined with the 2nd Fleet and British ships in Atlantic exercises and with NATO forces in the eastern Mediterranean during the fall of 1959. In December she aided victims of a disastrous flood at Fréjus, France.

In the spring of 1960, she was converted into an ASW Support Carrier and was thereafter homeported at Quonset Point, Rhode Island. Since that time she operated as the flagship of CarDiv 18 and Antisubmarine Carrier Group Three. She conducted rescue and salvage operations off the New Jersey coast for a downed blimp; cruised with midshipmen, and was deployed on NATO and CENTO exercises that took her through the Suez Canal into the Indian Ocean. Ports of call included Karachi and the British Crown Colony of Aden. In November she joined the French navy in Operation "Jet Stream".

Essex underway, 1960.

In April 1961, Essex steamed out of Naval Station Mayport,

Florida on a two-week "routine training" cruise, purportedly to support

the carrier qualification of a squadron of Navy pilots. Twelve A4D-2 Skyhawks had been loaded aboard, the aircraft, pilots and support crews all from attack squadron VA-34, the Blue Blasters.

The A4D-2Ns were armed with 20 mm cannon, and after several days at sea

all their identifying markings were crudely obscured with flat gray

paint. They began flying mysterious missions day and night with at least

one returning bearing battle damage. Not generally known to Essex crew was that they had been tasked to provide air support to CIA-sponsored bombers during the ill-fated Bay of Pigs Invasion. The naval aviation part of the mission was aborted by President Kennedy at the last moment and the Essex crew sworn to secrecy.[1]

Essex underway, 1960.

In April 1961, Essex steamed out of Naval Station Mayport,

Florida on a two-week "routine training" cruise, purportedly to support

the carrier qualification of a squadron of Navy pilots. Twelve A4D-2 Skyhawks had been loaded aboard, the aircraft, pilots and support crews all from attack squadron VA-34, the Blue Blasters.

The A4D-2Ns were armed with 20 mm cannon, and after several days at sea

all their identifying markings were crudely obscured with flat gray

paint. They began flying mysterious missions day and night with at least

one returning bearing battle damage. Not generally known to Essex crew was that they had been tasked to provide air support to CIA-sponsored bombers during the ill-fated Bay of Pigs Invasion. The naval aviation part of the mission was aborted by President Kennedy at the last moment and the Essex crew sworn to secrecy.[1]

Later in 1961, Essex completed a "People to People" cruise to Northern Europe with ports of call in Rotterdam, Hamburg, and Greenock, Scotland. During the Hamburg visit over one million visitors toured Essex. During her departure, Essex almost ran aground in the shallow Elbe River. On her return voyage to CONUS, she ran into a severe North Atlantic storm (January 1962) and suffered major structural damage. In early 1962, she went into drydock in the Brooklyn Navy Yard for a major overhaul.

Essex had just finished her six-month long overhaul and was at Guantanamo Bay Naval Base for sea trials when President John F. Kennedy placed a naval "quarantine" on Cuba in October 1962, in response to the discovered presence of Soviet missiles in that country (see Cuban Missile Crisis). (The word quarantine was used rather than blockade for reasons of international law—Kennedy reasoned that a blockade would be an act of war, and war had not been declared between the U.S. and Cuba.)[2] Essex spent over a month in the Caribbean as one of the US Navy ships enforcing this "quarantine", returning home just before Thanksgiving.

The Apollo 7 crew is welcomed aboard the USS Essex.

Essex was scheduled to be the prime recovery carrier for the ill fated Apollo 1 space mission. It was to pick up Apollo 1 astronauts north of Puerto Rico on 7 March 1967 after a 14-day spaceflight. However, the mission did not take place because on 27 January 1967, the Apollo 1's crew was killed by a flash fire in their spacecraft on LC-34 at the Cape Canaveral Air Force Station, Florida.

The Apollo 7 crew is welcomed aboard the USS Essex.

Essex was scheduled to be the prime recovery carrier for the ill fated Apollo 1 space mission. It was to pick up Apollo 1 astronauts north of Puerto Rico on 7 March 1967 after a 14-day spaceflight. However, the mission did not take place because on 27 January 1967, the Apollo 1's crew was killed by a flash fire in their spacecraft on LC-34 at the Cape Canaveral Air Force Station, Florida.

Essex was the prime recovery carrier for the Apollo 7 mission. She recovered the Apollo 7's crew on 22 October 1968 after a splashdown north of Puerto Rico.

Essex was the main vessel on which future Apollo 11 astronaut Neil Armstrong served during the Korean War.

Essex was decommissioned on 30 June 1969 and was moored at the Boston Navy Yard. She was struck from the Naval Vessel Register on 1 June 1973, and sold by the Defense Reutilization and Marketing Service (DRMS) for scrapping on 1 June 1975.

This article incorporates text from the public domain Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. The entry can be found here.

Construction and Commissioning

Essex was laid down on 28 April 1941 by Newport News Shipbuilding and Dry Dock Co. After the Pearl Harbor attack her building contract (along with the same for CV-10 and CV-12) was reworked. After an accelerated construction, she was launched on 31 July 1942, sponsored by Mrs. Artemus L. Gates, the wife of the Assistant Secretary of the Navy for Air. She was commissioned on 31 December 1942 with Captain Donald B. Duncan commanding.Service history

World War II

Essex — in TG 58.2 – now joined with TG 58.1 and TG 58.3 to constitute Task Force 58 (the "Fast Carrier Task Force"), to launch an attack against Truk (17–18 February) during which eight Japanese ships were sunk. En route to the Mariana Islands to sever Japanese supply lines, the carrier force was detected and received a prolonged aerial attack which it repelled in a businesslike manner and then continued with the scheduled attack upon Saipan, Tinian and Guam (23 February).

After this operation, Essex proceeded to San Francisco for her single wartime overhaul. Following her overhaul, Essex became the carrier for Air Group 15, the "Fabled Fifteen," commanded by the U.S. Navy's top ace of the war, David McCampbell. She then joined carriers Wasp and San Jacinto in TG 12.1 to strike Marcus Island (19–20 May) and Wake (23 May). She deployed with TF 58 to support the occupation of the Marianas (12 June – 10 August); sortied with TG 38.3 to lead an attack against the Palau Islands (6–8 September), and Mindanao (9–10 September) with enemy shipping as the main target, and remained in the area to support landings on Peleliu. On 2 October, she weathered a typhoon and four days later departed with Task Force 38 (TF 38) for the Ryukyus. (TF 38 was actually the same formation as TF 58, the nomenclature being changed to reflect the rotation of command staffs employed by the Navy for efficiency in executing multiple operations; this rotation allowed constant front-line deployment of the ships and their crews while providing operational planning time at better-equipped, rear-area base facilities for the command structure not currently afloat).

For the remainder of 1944, she continued her frontline action, participating in strikes against Okinawa (10 October), and Formosa (12–14 October), covering the Leyte landings, taking part in the Battle for Leyte Gulf (24–25 October), and continuing the search for enemy fleet units until 30 October, when she returned to Ulithi, Caroline Islands, for replenishment. She resumed the offensive and delivered attacks on Manila and the northern Philippine Islands during November. On 25 November, for the first time in her far-ranging operations and destruction to the enemy, Essex received damage. A kamikaze hit the port edge of her flight deck landing among planes gassed for takeoff, causing extensive damage, killing 15, and wounding 44.

For the remainder of the war, she operated with TF 58, conducting attacks against the Tokyo area (16–17, and 25 February) both to neutralize the enemy's air power before the landings on Iwo Jima and to cripple the aircraft manufacturing industry. She sent support missions against Iwo Jima and neighboring islands, but from 23 March – 28 May was employed primarily to support the conquest of Okinawa.

Korean War

On 1 December 1953, she started her final tour of the war, sailing in the East China Sea with what official U.S. Navy records describe as the "Peace Patrol". From November 1954 – June 1955, she engaged in training exercises, operated for three months with the United States Seventh Fleet, assisted in the Tachen Islands evacuation, and engaged in air operations and fleet maneuvers off Okinawa.

Pacific Fleet

In July 1955, Essex entered Puget Sound Naval Shipyard for repairs and extensive alterations. The SCB-125 modernization program included installation of an angled flight deck and an enclosed hurricane bow, as well as relocation of the aft elevator to the starboard deck edge. Modernization completed, she rejoined the Pacific Fleet in March 1956. For the next 14 months, the carrier operated off the West Coast, except for a six-month cruise with the 7th Fleet in the Far East. Ordered to join the Atlantic Fleet for the first time in her long career, she sailed from San Diego on 21 June 1957, rounded Cape Horn, and arrived in Mayport, Florida on 1 August.Atlantic and Mediterranean

Essex joined with the 2nd Fleet and British ships in Atlantic exercises and with NATO forces in the eastern Mediterranean during the fall of 1959. In December she aided victims of a disastrous flood at Fréjus, France.

In the spring of 1960, she was converted into an ASW Support Carrier and was thereafter homeported at Quonset Point, Rhode Island. Since that time she operated as the flagship of CarDiv 18 and Antisubmarine Carrier Group Three. She conducted rescue and salvage operations off the New Jersey coast for a downed blimp; cruised with midshipmen, and was deployed on NATO and CENTO exercises that took her through the Suez Canal into the Indian Ocean. Ports of call included Karachi and the British Crown Colony of Aden. In November she joined the French navy in Operation "Jet Stream".

Bay of Pigs and Cuban Missile Crisis

Later in 1961, Essex completed a "People to People" cruise to Northern Europe with ports of call in Rotterdam, Hamburg, and Greenock, Scotland. During the Hamburg visit over one million visitors toured Essex. During her departure, Essex almost ran aground in the shallow Elbe River. On her return voyage to CONUS, she ran into a severe North Atlantic storm (January 1962) and suffered major structural damage. In early 1962, she went into drydock in the Brooklyn Navy Yard for a major overhaul.

Essex had just finished her six-month long overhaul and was at Guantanamo Bay Naval Base for sea trials when President John F. Kennedy placed a naval "quarantine" on Cuba in October 1962, in response to the discovered presence of Soviet missiles in that country (see Cuban Missile Crisis). (The word quarantine was used rather than blockade for reasons of international law—Kennedy reasoned that a blockade would be an act of war, and war had not been declared between the U.S. and Cuba.)[2] Essex spent over a month in the Caribbean as one of the US Navy ships enforcing this "quarantine", returning home just before Thanksgiving.

Nautilus incident

While conducting replenishment exercises with NATO forces in November 1966, Essex collided with the submerged submarine USS Nautilus (SSN-571). The Nautilus sustained extensive sail damage, returning to port unassisted. Aboard Essex, the hull was opened and the ship's speed indicator equipment was destroyed, but the carrier was still able to make port unassisted. Essex subsequently reported to the Boston Naval Shipyard for extensive overhaul and hull repairs.Apollo missions

Essex was the prime recovery carrier for the Apollo 7 mission. She recovered the Apollo 7's crew on 22 October 1968 after a splashdown north of Puerto Rico.

Essex was the main vessel on which future Apollo 11 astronaut Neil Armstrong served during the Korean War.

Decommissioning and Disposal

Awards

- Presidential Unit Citation

- Navy Unit Commendation

- Meritorious Unit Citation

- Navy Expeditionary Medal (two awards)

- Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal with 13 battle stars

- World War II Victory Medal

- Navy Occupation Medal with "ASIA" clasp

- China Service Medal

- National Defense Service Medal with star (two awards)

- Korean Service Medal with four battle stars

- Armed Forces Expeditionary Medal with two stars (three awards)

- Philippine Presidential Unit Citation

- Philippine Liberation Medal

- United Nations Service Medal

Notes

- Wyden (1979), pp.125–127, 130, 214, 240–241.

- Kennedy, Robert F. (1969)

References

- Kennedy, Robert F. Thirteen Days: A Memoir of the Cuban Missile Crisis. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 1969. ISBN 978-0-333-10312-8.

- Wyden, Peter. Bay of Pigs: The Untold Story. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1979. ISBN 0-671-24006-4, ISBN 0-224-01754-3, ISBN 978-0-671-24006-6.

- Hansen, James R. First Man: The Life of Neil Armstrong. New York: Simon and Schuster, 2005. ISBN 978-0-7432-5631-5 (hardback), ISBN 978-0-7434-9232-4 (Pocket Books, 2006)

Labels:

download papercraft,

military paper model,

USS Essex

F-14 Tomcat

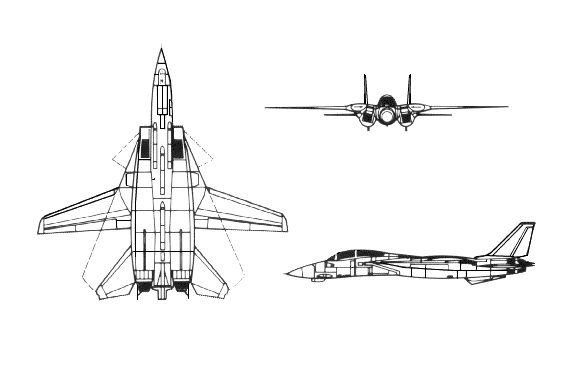

The F-14 first flew in December 1970 and made its first deployment in 1974 with the U.S. Navy aboard USS Enterprise (CVN-65), replacing the McDonnell Douglas F-4 Phantom II. The F-14 served as the U.S. Navy's primary maritime air superiority fighter, fleet defense interceptor and tactical reconnaissance platform. In the 1990s, it added the Low Altitude Navigation and Targeting Infrared for Night (LANTIRN) pod system and began performing precision ground-attack missions.[1]

| F-14 Tomcat | |

|---|---|

|

|

| A U.S. Navy F-14D conducts a mission over the Persian Gulf-region in 2005. | |

| Role | Interceptor, air superiority and multirole combat aircraft |

| National origin | United States of America |

| Manufacturer | Grumman Aerospace Corporation |

| First flight | 21 December 1970 |

| Introduction | 22 September 1974 |

| Retired | 22 September 2006 (United States Navy) |

| Status | In service with the Iranian Air Force |

| Primary users | United States Navy (historical) Imperial Iranian Air Force (historical) Islamic Republic of Iran Air Force |

| Produced | 1969–1991 |

| Number built | 712 |

| Unit cost |

US$38 million (1998)

|

Development

Background

Beginning in the late 1950s, the U.S. Navy sought a long-range, high-endurance interceptor to defend its carrier battle groups against long-range anti-ship missiles launched from the jet bombers and submarines of the Soviet Union. The U.S. Navy needed a Fleet Air Defense (FAD) aircraft with a more powerful radar, and longer range missiles than the F-4 Phantom II to intercept both enemy bombers and missiles.[3] The Navy was directed to participate in the Tactical Fighter Experimental (TFX) program with the U.S. Air Force by Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara. McNamara wanted "joint" solutions to service aircraft needs to reduce development costs, and had already directed the Air Force to buy the F-4 Phantom II, which was developed for the Navy and Marine Corps.[4] The Navy strenuously opposed the TFX as it feared compromises necessary for the Air Force's need for a low-level attack aircraft would adversely impact the aircraft's performance as a fighter .

VFX

The F-111B had been designed for the long-range Fleet Air Defense (FAD) interceptor role, but not for new requirements for air combat based on experience of American aircraft against agile MiG fighters over Vietnam. The Navy studied the need for VFAX, an additional fighter that was more agile than the F-4 Phantom for air-combat and ground-attack roles.[7] Grumman continued work on its 303 design and offered it to the Navy in 1967, which led to fighter studies by the Navy. The company continued to refine the design into 1968.[5]In July 1968, the Naval Air Systems Command (NAVAIR) issued a request for proposals (RFP) for the Naval Fighter Experimental (VFX) program. VFX called for a tandem two-seat, twin-engined air-to-air fighter with a maximum speed of Mach 2.2. It would also have a built-in M61 Vulcan cannon and a secondary close air support role.[8] The VFX's air-to-air missiles would be either six AIM-54 Phoenix or a combination of six AIM-7 Sparrow and four AIM-9 Sidewinder missiles. Bids were received from General Dynamics, Grumman, Ling-Temco-Vought, McDonnell Douglas and North American Rockwell;[9] four bids incorporated variable-geometry wings.[8][N 1]

Upon winning the contract for the F-14, Grumman greatly expanded its Calverton, Long Island, New York facility for evaluating the aircraft. Much of the testing, including the first of many compressor stalls and multiple ejections, took place over Long Island Sound. In order to save time and forestall interference from Secretary McNamara, the Navy skipped the prototype phase and jumped directly to full-scale development; the Air Force took a similar approach with its F-15.[13] The F-14 first flew on 21 December 1970, just 22 months after Grumman was awarded the contract, and reached initial operational capability (IOC) in 1973. The United States Marine Corps was initially interested in the F-14 as an F-4 Phantom II replacement; going so far as to send officers to Fighter Squadron One Twenty-Four (VF-124) to train as instructors. The marine corps pulled out of any procurement when development of the stores management system for ground attack munitions was not pursued. An air-to-ground capability was not developed until the 1990s.[13]

Firing trials involved launches against simulated targets of various types, from cruise missiles to high-flying bombers. AIM-54 Phoenix missile testing from the F-14 began in April 1972. The longest single Phoenix launch was successful against a target at a range of 110 nmi (200 km) in April 1973. Another unusual test was made on 22 November 1973, when six missiles were fired within 38 seconds at Mach 0.78 and 24,800 ft (7,600 m); four scored direct hits.[14]

Improvements and changes

With time, the early versions of all the missiles were replaced by more advanced versions, especially with the move to full solid-state electronics that allowed better reliability, better ECCM and more space for the rocket engine. So the early arrangement of the AIM-54A Phoenix active-radar air-to-air missile, the AIM-7E-2 Sparrow Semi-active radar homing air-to-air missile, and the AIM-9J Sidewinder heat-seeking air-to-air missile was replaced in the 1980s with the B (1983) and C (1986) version of the Phoenix, the F (1977), M (1982), P (1987 or later) for Sparrows, and with the Sidewinder, L (1979) and M (1982). Within these versions there are several improved batches (for example, Phoenix AIM-54C++).[15]The Tactical Airborne Reconnaissance Pod System (TARPS) was developed in the late 1970s for the F-14. Approximately 65 F-14As and all F-14Ds were modified to carry the pod.[16] TARPS was primarily controlled by the Radar Intercept Officer (RIO), who had a specialized display to observe reconnaissance data. The TARPS was upgraded with digital camera in 1996 with the "TARPS Digital (TARPS-DI)". The digital camera was further updated beginning in 1998 with the "TARPS Completely Digital (TARPS-CD)" configuration that provided real-time transmission of imagery.[17]

Some of the F-14A aircraft underwent engine upgrades to the GE F110-400 in 1987. These upgraded Tomcats were redesignated F-14A+, which was later changed to F-14B in 1991.[18] The F-14D variant was developed at the same time; it included the GE F110-400 engines with newer digital avionics systems such as a glass cockpit, and compatibility with the Link 16 secure datalink.[19] The Digital Flight Control System (DFCS) notably improved the F-14's handling qualities when flying at a high angle of attack or in air combat maneuvering.[20]

Adding ground attack capability

By 1994, Grumman and the Navy were proposing ambitious plans for Tomcat upgrades to plug the gap between the retirement of the A-6 and the F/A-18E/F Super Hornet entering service. However, the upgrades would have taken too long to implement to meet the gap, and were priced in the billions; Congress considered this too expensive for an interim solution.[16] A quick, inexpensive upgrade using the Low Altitude Navigation and Targeting Infrared for Night (LANTIRN) targeting pod was devised. The LANTIRN pod provided the F-14 with a forward-looking infrared (FLIR) camera for night operations and a laser target designator to direct laser-guided bombs (LGB).[21] Although LANTIRN is traditionally a two-pod system, an AN/AAQ-13 navigation pod with terrain-following radar and a wide-angle FLIR, along with an AN/AAQ-14 targeting pod with a steerable FLIR and a laser target designator, the decision was made to only use the targeting pod. The Tomcat's LANTIRN pod was altered and improved over the baseline configuration, such as a Global Positioning System / Inertial Navigation System (GPS-INS) capability to allow an F-14 to accurately locate itself. The pod was carried on the right wing glove pylon.[21]

An upgraded LANTIRN named "LANTIRN 40K" for operations up to 40,000 ft (12,000 m) was introduced in 2001, followed by Tomcat Tactical Targeting (T3) and Fast Tactical Imagery (FTI), to provide precise target coordinate determination and ability to transmit images in-flight.[24] Tomcats also added the ability to carry the GBU-38 Joint Direct Attack Munition (JDAM) in 2003, giving it the option of a variety of LGB and GPS-guided weapons.[25] Some F-14Ds were upgraded in 2005 with a ROVER III Full Motion Video (FMV) downlink, a system that transmits real-time images from the aircraft's sensors to the laptop of Forward Air Controller (FAC) on the ground.[26]

Design

Overview

The F-14's fuselage and wings allow it to climb faster than the F-4, while the twin-tail arrangement offers better stability. The F-14 is equipped with an internal 20 mm M61 Vulcan Gatling cannon mounted on the left side, and can carry AIM-54 Phoenix, AIM-7 Sparrow, and AIM-9 Sidewinder anti-aircraft missiles. The twin engines are housed in nacelles, spaced apart by 1 to 3 ft (0.30 to 0.91 m). The flat area of the fuselage between the nacelles is used to contain fuel and avionics systems such as the wing-sweep mechanism and flight controls, and the underside used to carry the F-14's complement of Phoenix or Sparrow missiles, or assorted bombs.[15] By itself, the fuselage provides approximately 40 to 60 percent of the F-14's aerodynamic lifting surface depending on the wing sweep position.[30]

Variable-geometry wings

The F-14's wing sweep can be varied between 20° and 68° in flight,[31] and can be automatically controlled by the Central Air Data Computer, which maintains wing sweep at the optimum lift-to-drag ratio as the Mach number varies; pilots can manually override the system if desired.[15] When parked, the wings can be "overswept" to 75° to overlap the horizontal stabilizers to save deck space aboard carriers. In an emergency, the F-14 can land with the wings fully swept to 68°,[15] although this presents a significant safety hazard due to greatly increased airspeed. Thus an aircraft would typically be diverted from an aircraft carrier to a land base if an incident did occur. The F-14 has flown and landed safely with an asymmetrical wing-sweep on an aircraft carrier during testing; this capability could be used in emergencies.[32]

Two triangular shaped retractable surfaces, called glove vanes, were originally mounted in the forward part of the wing glove, and could be automatically extended by the flight control system at high Mach numbers. They were used to generate additional lift ahead of the aircraft's center of gravity, thus helping to compensate for the nose-down pitching tendencies at supersonic speeds. Automatically deployed at above Mach 1.4, they allowed the F-14 to pull 7.5 g at Mach 2 and could be manually extended with wings swept full aft. They were later disabled, however, owing to their additional weight and complexity.[15] The air brakes consist of top-and-bottom extendable surfaces at the rearmost portion of the fuselage, between the engine nacelles. The bottom surface is split into left and right halves, the arrestor hook hangs between the two halves, an arrangement sometimes called the "castor tail".[33]

Engines and landing gear

The F-14 was initially equipped with two Pratt & Whitney TF30 (or JT10A) turbofan engines, providing a total thrust of 20,900 lb (93 kN) and giving the aircraft an official maximum speed of Mach 2.34.[34] However, the F-14 would normally fly at a cruising speed for reduced fuel consumption, which was important for conducting lengthy patrol missions.[35] Both of the engine's rectangular air intakes were equipped with movable ramps and bleed doors to meet the airflow requirements of the engine but prevent dangerous shockwaves from entering. Variable nozzles were also fitted to the engine's exhaust.

The landing gear is very robust, in order to withstand the harsh takeoffs and landings necessary for carrier operation. It comprises a double nosewheel and widely spaced single main wheels. There are no hardpoints on the sweeping parts of the wings, and so all the armament is fitted on the belly between the air intakes and on pylons under the wing gloves. Internal fuel capacity is 2,400 US gal (9,100 l): 290 US gal (1,100 l) in each wing, 690 US gal (2,600 l) in a series of tanks aft of the cockpit, and a further 457 US gal (1,730 l) in two feeder tanks. It can carry two 267 US gal (1,010 l) external drop tanks under the engine intakes.[15] There is also an air-to-air refueling probe, which folds into the starboard nose.[36]

Avionics and flight controls

The cockpit has two seats, arranged in tandem, outfitted with Martin-Baker GRU-7A rocket-propelled ejection seats, rated from zero altitude and zero airspeed up to 450 knots.[37] The canopy is spacious, and fitted with four mirrors to provide effectively all-round visibility. Only the pilot has flight controls; the flight instruments themselves are of a hybrid analog-digital nature.[15] The cockpit also features a head-up display (HUD) to show primarily navigational information; several other avionics systems such as communications and direction-finders are integrated into the AWG-9 radar's display. A significant feature of the F-14 was its Central Air Data Computer (CADC), designed by Garrett AiResearch, that formed the onboard integrated flight control system. It used a MOS-based LSI chipset, the MP944, making it possibly the first microprocessor in history.[38]

The F-14 also features electronic countermeasures (ECM) and radar warning (RWR) systems, chaff/flare dispensers, fighter-to-fighter data link, and a precise inertial navigation system.[15] The early navigation system was inertial-based, point-of-origin coordinates were programmed into a navigation computer and gyroscopes would track the aircraft's every motion to calculate distance and direction from that starting point. GPS later was integrated to provide more precise navigation and redundancy in case either system failed. The chaff/flare dispensers were located on the underside of the fuselage and on the tail. The RWR system consisted of several antennas on the aircraft's fuselage, which could roughly calculate both direction and distance of enemy radar users; it could also differentiate between search radar, tracking radar, and missile-homing radar.[40]

Featured in the sensor suite was the AN/ALR-23, an infrared sensor using indium antimonide detectors, mounted under the nose; however this was replaced by an optical system, Northrop's AAX-1, also designated TCS (TV Camera Set). The AAX-1 helped pilots visually identify and track aircraft, up to a range of 60 miles (97 km) for large aircraft. The radar and the AAX-1 were linked, allowing the one detector to follow the direction of the other. A dual infrared/optical detection system was adopted on the later F-14D.[citation needed]

Armament

The F-14 was designed to combat highly maneuverable aircraft as well as the Soviet cruise missile and bomber threats.[29] The Tomcat was to be a platform for the AIM-54 Phoenix, but unlike the canceled F-111B, it could also engage medium- and short-range threats with other weapons.[27][29] The F-14 was an air superiority fighter, not just a long-range interceptor.[29] Over 6,700 kg (14,800 lb) of stores could be carried for combat missions on several hardpoints under the fuselage and under the wings. Commonly, this meant a maximum of two–four Phoenixes or Sparrows on the belly stations, two Phoenixes/Sparrows on the wing hardpoints, and two Sidewinders on the wing hardpoints.[citation needed] The F-14 was also fitted with an internal 20 mm M61 Vulcan Gatling-type cannon.Operationally, the capability to hold up to six Phoenix missiles was never used, although early testing was conducted; there was never a threat requirement to engage six hostile targets simultaneously and the load was too heavy to safely recover aboard an aircraft carrier in the event that the missiles were not fired. During the height of Cold War operations in the late 1970s and 1980s, the typical weapon loadout on carrier-deployed F-14s was usually only one AIM-54 Phoenix, augmented by two AIM-9 Sidewinders, two AIM-7 Sparrow IIIs, a full loadout of 20 mm ammunition and two drop tanks.[citation needed] The Phoenix missile was used twice in combat by the U.S. Navy, both over Iraq in 1999,[41][42][43] but the missiles did not score any kills.

Operational history

Main article: F-14 Tomcat operational history

United States Navy

Its first sustained combat use was as a photo reconnaissance platform. The Tomcat was selected to inherit the reconnaissance mission upon departure of the dedicated RA-5C Vigilante and RF-8G Crusaders from the fleet. A large pod called the Tactical Airborne Reconnaissance Pod System (TARPS) was developed and fielded on the Tomcat in 1981. With the retirement of the last RF-8G Crusaders in 1982, TARPS F-14s became the U.S. Navy's primary tactical reconnaissance system.[44] One of two Tomcat squadrons per airwing was designated as a TARPS unit and received 3 TARPS capable aircraft and training for 4 TARPS aircrews.

In 1995, F-14s from VF-14 and VF-41 participated in Operation Deliberate Force as well as Operation Allied Force in 1999, and in 1998, VF-32 and VF-213 participated in Operation Desert Fox. On 15 February 2001 the Joint Direct Attack Munition or JDAM was added to the Tomcat's arsenal. On 7 October 2001, F-14s would lead some of the first strikes into Afghanistan marking the start of Operation Enduring Freedom and the first F-14 drop of a JDAM occurred on 11 March 2002. F-14s from VF-2, VF-31, VF-32, VF-154, and VF-213 would also participate in Operation Iraqi Freedom. The F-14Ds of VF-2, VF-31, and VF-213 obtained JDAM capability in March 2003.[25] On 10 December 2005, the F-14Ds of VF-31 and VF-213 were upgraded with a ROVER III downlink for transmitting images to a ground Forward Air Controller (FAC).[26]

The last American F-14 combat mission was completed on 8 February 2006, when a pair of Tomcats landed aboard the USS Theodore Roosevelt (CVN-71) after one dropped a bomb over Iraq. During their final deployment with the USS Theodore Roosevelt (CVN-71), VF-31 and VF-213 collectively completed 1,163 combat sorties totaling 6,876 flight hours, and dropped 9,500 lb (4,300 kg) of ordnance during reconnaissance, surveillance, and close air support missions in support of Operation Iraqi Freedom.[50] The USS Theodore Roosevelt (CVN-71) launched an F-14D, of VF-31, for the last time on 28 July 2006; piloted by Lt. Blake Coleman and Lt. Cmdr Dave Lauderbaugh as RIO.[51]

The official final flight retirement ceremony was on 22 September 2006 at Naval Air Station Oceana, and was flown by Lt. Cmdr. Chris Richard and Lt. Mike Petronis as RIO in a backup F-14 after the primary aircraft experienced mechanical problems.[52][53] The actual last flight of an F-14 in U.S. service took place 4 October 2006, when an F-14D of VF-31 was ferried from NAS Oceana to Republic Airport on Long Island, New York.[53] The remaining intact F-14 aircraft in the U.S. were flown to and stored at the 309th Aerospace Maintenance and Regeneration Group "Boneyard", at Davis-Monthan Air Force Base, Arizona; as of 2007 the aircraft were to be shredded to prevent any components from being acquired by Iran.[54] In August 2009, the 309th AMARG announced that the last of the F-14's planned for scrapping were taking to HVF West, Tucson, Arizona for shredding. At that time only 11 F-14's remained in desert storage.[55]

Iran

The first F-14 arrived in January 1976, modified only by the removal of classified avionics components, but fitted with the TF-30-414 engines. The following year 12 more were delivered. Meanwhile, training of the first groups of Iranian crews by the U.S. Navy, was underway in the USA; and one of these conducted a successful shoot-down with a Phoenix missile of a target drone flying at 50,000 ft (15 km).

Following the overthrow of the Shah in 1979, the air force was renamed the Islamic Republic of Iran Air Force (IRIAF) and the post-revolution interim government of Iran canceled most Western arms orders. In 1980 an Iranian F-14 shot down an Iraqi Mil Mi-25 helicopter for its first air-to-air kill during the Iran-Iraq conflict.[56]

Between 1982 and 1986 Iranian Tomcats were to see use in a series of slowly developing campaigns: mainly tasked with patrolling the skies over objects vital for the survival of Iranian regime and economy, like Tehran or Kharg Island. Most of these patrols were supported by Boeing 707-3J9C tankers, and some lasted as long as 10 hours with up to four in-flight refuelings. Time and again, they were involved in new air battles, and performed well but their main role was intimidating the Iraqi Air Force. Cognizant of previous heavy losses in battles against Iranian F-14s, the Iraqis avoided any engagement with them, so that the sole presence of a Tomcat over the target area was enough to force Iraqi formations to abort their attacks. Because of this, and because of the precision and effectiveness of the Tomcat's AWG-9 weapons system and AIM-54A Phoenix long-range air-to-air missiles, the F-14 maintained air control over a lengthy period of time.[citation needed]

Overall, Tom Cooper claims that Iranian F-14s shot down at least 160 Iraqi aircraft during the Iran-Iraq War, which include 58 MiG-23s, 23 MiG-21s, nine MiG-25s, 33 Dassault Mirage F1s, 23 Su-17s, one Mil Mi-24, five Tu-22s, two MiG-27s, one Dassault Mirage 5, one B-6D, one Aérospatiale Super Frelon, and two unknown aircraft. Despite the circumstances under which the F-14s and their crews had to operate in Iran during the eight-year long war against Iraq, it is still the premier fighter in the Iranian Air Force. The aircraft continued to operate without any support from AWACS or AEW aircraft, without even a proper support from the Ground Control Intercept(GCI). It faced an enemy that was repeatedly introducing new and more capable fighters, radars, weapons and ECM systems in combat and was supported by no less than three "superpowers" (France, the USA, and the USSR). Their crews were also permanently under heavy pressure from the regime in Tehran. That it proved as successful in combat is a result of strenuous efforts of IRIAF personnel and immense investment of the Iranian economy.[56]

On 31 August 1986, an Iranian F-14A armed with at least one AIM-54A missile defected to Iraq. In addition, one or more of Iran's F-14A was delivered to the Soviet Union in exchange for technical assistance; at least one of its crew defected to the Soviet Union.[58]

Iran had an estimated 44 F-14s in 2009;[59] It has 19 F-14s in operation in January 2013, according to estimate by Aviation Week.[60]

In January 2007, the U.S. Department of Defense announced that sales of spare F-14 parts would be suspended over concerns of the parts ending up in Iran.[61] In July 2007, the remaining American F-14s were shredded to ensure that any parts could not be acquired.[54] In summer of 2010, Iran requested that the United States deliver the 80th F-14 it had purchased in 1974, but delivery was denied after the Islamic Revolution.[62][63] In October 2010, an Iranian Air Force commander claimed that the country overhauls and optimizes different types of military aircraft, mentioning that Air Force has even installed Iran-made radar systems on the F-14.[64]

On 26 January 2012, an Iranian F-14 crashed three minutes after takeoff. Both crew members were killed.[65]

Variants

A total of 712 F-14s were built[66] from 1969 to 1991.[67] F-14 assembly and test flights were performed at Grumman's plant in Calverton on Long Island, NY. Grumman facility at nearby Bethpage, NY was directly involved in F-14 manufacturing and was home to its engineers. The airframes were partially assembled in Bethpage and then shipped to Calverton for final assembly. Various tests were also performed at the Bethpage Plant. Over 160 of the U.S. aircraft were destroyed in accidents.[68]

F-14A

The F-14A was the initial two-seat all-weather interceptor fighter variant for the U.S. Navy. It first flew on 21 December 1970. The first 12 F-14As were prototype versions[69] (sometimes called YF-14As). Modifications late in its service life added precision strike munitions to its armament. The U.S. Navy received 478 F-14A aircraft and 79 were received by Iran.[66] The final 102 F-14As were delivered with improved TF30-P-414A engines.[70] Additionally, an 80th F-14A was manufactured for Iran, but was delivered to the U.S. Navy.[66]F-14B

The F-14 received its first of many major upgrades in March 1987 with the F-14A Plus (or F-14A+). The F-14A's P&W TF30 engine was replaced with the improved GE F110-GE400 engine. The F-14A+ also received the state-of-the-art ALR-67 Radar Homing and Warning (RHAW) system. Much of the avionics as well as the AWG-9 radar were retained. The F-14A+ was later redesignated F-14B on 1 May 1991. A total of 38 new aircraft were manufactured and 48 F-14A were upgraded into B variants.[18]The TF30 had been plagued from the start with susceptibility to compressor stalls at high AoA and during rapid throttle transients or above 30,000 ft (9,100 m). The F110-GE400 engine provided a significant increase in thrust, producing 30,200 lbf (134 kN) with afterburner at sea level. The increased thrust gave the Tomcat a better than 1:1 thrust-to-weight ratio at low fuel quantities. The basic engine thrust without afterburner was powerful enough for carrier launches, further increasing safety. Another benefit was allowing the Tomcat to cruise comfortably above 30,000 ft (9,100 m), which increased its range and survivability. The F-14B arrived in time to participate in Desert Storm.

In the late 1990s, 67 F-14Bs were upgraded to extend airframe life and improve offensive and defensive avionics systems. The modified aircraft became known as F-14B Upgrade or as "Bombcat".[70]

F-14D

The final variant of the F-14 was the F-14D Super Tomcat. The F-14D variant was first delivered in 1991. The original TF-30 engines were replaced with GE F110-400 engines, similar to the F-14B. The F-14D also included newer digital avionics systems including a glass cockpit and replaced the AWG-9 with the newer AN/APG-71 radar. Other systems included the Airborne Self Protection Jammer (ASPJ), Joint Tactical Information Distribution System (JTIDS), SJU-17(V) Naval Aircrew Common Ejection Seats (NACES) and Infra-red search and track (IRST).[71]

While upgrades had kept the F-14 competitive with modern fighter aircraft technology, Cheney called the F-14 1960s technology. Despite an appeal from the Secretary of the Navy for at least 132 F-14Ds and some aggressive proposals from Grumman for a replacement,[72] Cheney planned to replace the F-14 with a fighter that was not manufactured by Grumman. Cheney called the F-14 a "jobs program", and when the F-14 was canceled, an estimated 80,000 jobs of Grumman employees, subcontractors, or support personnel were affected.[73] Starting in 2005, some F-14Ds received the ROVER III upgrade.

Projected variants

The first F-14B was to be an improved version of the F-14A with more powerful "Advanced Technology Engine" F401 turbofans. The F-14C was a projected variant of this initial F-14B with advanced multi-mission avionics.[74] Grumman also offered an interceptor version of the F-14B in response to the U.S. Air Force's Improved Manned Interceptor Program to replace the Convair F-106 Delta Dart as an Aerospace Defense Command interceptor in the 1970s. The F-14B program was terminated in April 1974.[75]

The last "Tomcat" variant was the ASF-14 (Advanced Strike Fighter-14), Grumman's replacement for the NATF concept. By all accounts, it would not be even remotely related to the previous Tomcats save in appearance, incorporating the new technology and design know-how from the Advanced Tactical Fighter (ATF) and Advanced Tactical Aircraft (ATA) programs. The ASF-14 would have been a new-build aircraft; however, its projected capabilities were not that much better than that of the (A)ST-21 variants.[77] In the end the Attack Super Tomcat was considered to be too costly. The Navy decided to pursue the cheaper F/A-18E/F Super Hornet to fill the fighter-attack role.[76]

Operators

Iran

- Islamic Republic of Iran Air Force

- 72nd TFS: F-14A, 1976–1985

- 73rd TFS: F-14A, 1977–1985

- 81st TFS: F-14A, 1977–present

- 82nd TFS: F-14A, 1978–present

- 83rd Tomcat Flight School: F-14A, 1978–1979

- 83rd TFS: F-14A, renamed former 62nd TFS[78]

United States

- United States Navy operated F-14 from 1974 to 2006

- Navy Fighter Weapons School (TOPGUN) (Merged with Strike University (Strike U) to form Naval Strike and Air Warfare Center (NSAWC) 1996)

- VF-126 Bandits (Disestablished 1 April 1994)

- VF-1 Wolfpack (Disestablished 30 September 1993)

- VF-2 Bounty Hunters (Pacific Fleet through 1996, Atlantic Fleet 1996-2003, Pacific Fleet 2003–present; redesignated VFA-2 with F/A-18F, 1 July 2003)

- VF-11 Red Rippers (Redesignated to VFA-11 with F/A-18F, May 2005)

- VF-14 Tophatters (Redesignated VFA-14 with F/A-18E, 1 December 2001, and transferred to Pacific Fleet, 2002)

- VF-21 Freelancers (Disestablished 31 January 1996)

- VF-24 Fighting Renegades (Disestablished 20 August 1996)

- VF-31 Tomcatters (Redesignated VFA-31 with F/A-18E, October 2006)

- VF-32 Swordsmen (Redesignated VFA-32 with F/A-18F, 1 October 2005)

- VF-33 Starfighters (Disestablished 1 October 1993)

- VF-41 Black Aces (Redesignated VFA-41 with F/A-18F, 1 December 2001)

- VF-51 Screaming Eagles (Disestablished 31 March 1995)

- VF-74 Bedevilers (Disestablished 30 April 1994)

- VF-84 Jolly Rogers (Disestablished 1 October 1995; squadron heritage and nickname transferred to VF-103)

- VF-102 Diamondbacks (Redesignated VFA-102 with F/A-18F, 1 May 2002, and transferred to Pacific Fleet)

- VF-103 Sluggers/Jolly Rogers (Redesignated VFA-103 with F/A-18F, 1 May 2005)

- VF-111 Sundowners (Disestablished 31 March 1995; reestablished as VFC-111 in Naval Air Force Reserve with Northrop F-5N and F-5F, 1 November 2006)

- VF-114 Aardvarks (Disestablished 30 April 1993)

- VF-142 Ghostriders (Disestablished 30 April 1995)

- VF-143 Pukin' Dogs (Redesignated VFA-143 with F/A-18E, early 2005)

- VF-154 Black Knights (Redesignated VFA-154 with F/A-18F, 1 October 2003)

- VF-191 Satan's Kittens (Disestablished 30 April 1988)

- VF-194 Red Lightnings (Disestablished 30 April 1988)

- VF-211 Fighting Checkmates (Pacific Fleet through 1996, then transferred to Atlantic Fleet; redesignated VFA-211 with F/A-18F, 1 October 2004)

- VF-213 Black Lions (Pacific Fleet through 1996, then transferred to Atlantic Fleet; redesignated VFA-213 with F/A-18F, May 2006)

- Navy Fighter Weapons School (TOPGUN) (Merged with Strike University (Strike U) to form Naval Strike and Air Warfare Center (NSAWC) 1996)

- Naval Air Systems Command Test and Evaluation Squadrons

- VX-4 Evaluators (Disestablished 30 September 1994 and merged into VX-5 to form VX-9)

- VX-9 Vampires (Currently operates F/A-18C/D/E/F, EA-18G, EA-6B, AV-8B, AH-1 and UH-1)

- VX-23 Salty Dogs (Currently operates F/A-18A+/B/C/D/E/F, EA-6B, EA-18G and T-45)

- VX-30 Bloodhounds (Currently operates P-3, C-130, S-3)

- Fleet Replacement Squadrons

- VF-101 Grim Reapers; Atlantic Fleet, then sole single-site, F-14 FRS (Disestablished 15 September 2005; reestablished as VFA-101, sole single-site F-35C Fleet Replacement Squadron in May 2012)[79]

- VF-124 Gunfighters; Pacific Fleet F-14 FRS

- (Disestablished 30 September 1994)

- Naval Air Force Reserve Squadrons

- VF-201 Hunters (Redesignated VFA-201 and reequipped with F/A-18A+ on 1 January 1999; disestablished 30 June 2007)

- VF-202 Superheats (Disestablished 31 December 1994)

- VF-301 Devil's Disciples (Disestablished 11 September 1994)

- VF-302 Stallions (Disestablished 11 September 1994)

- Naval Air Force Reserve Squadron Augmentation Units (SAUs)

- VF-1285 Fighting Fubijars (Disestablished September 1994);[80] augmented VF-301 and VF-302

- VF-1485 Americans (Disestablished September 1994);[81] augmented VF-124

- VF-1486 Fighting Hobos (Disestablished September 2005);[82] augmented VF-101

Aircraft on display

- Bureau Number (BuNo) – Model – Location – Significance

- F-14A

- 157982 - Cradle of Aviation Museum, Garden City, New York. Prototype #3 Nonstructural Demonstration Testbed.[83]

- 157984 - National Naval Aviation Museum, Naval Air Station Pensacola, Florida. Fifth F-14 manufactured and one of the prototypes used in flight testing. Mounted on pedestal at entrance to museum.[84]

- 157988 - NAS Oceana Air Park, Virginia.[85]

- 157990 - March Field Air Museum, Riverside, California.[86]

- 158623 - Naval Base Ventura County, NAS Point Mugu, California. Pedestal mount at Front Gate Airpark.[87]

- 158978 - USS Midway Museum, San Diego, California.[88]

- 158985 - Yanks Air Museum, Chino, California.[89]

- 158998 - Air Victory Museum, Lumberton, New Jersey.[90]

- 158999 - Naval Air Station Joint Reserve Base Fort Worth (former Carswell AFB), Fort Worth, Texas.[91]

- 159025 - Patriot's Point Naval and Maritime Museum, Charleston, South Carolina.[92]

- 159445 - Naval Station Norfolk (former Naval Air Station Norfolk) East Gate Airpark, Virginia.[93]

- 159448 - Naval Inventory Control Point, Pennsylvania.[94]

- 159455 - NAS Patuxent River, Lexington Park, Maryland. Former VX-23 flight test squadron aircraft.[95]

- 159600 - Fort Worth Aviation Museum, Fort Worth, Texas[96]

- 159620 - NAF El Centro, California.[97]

- 159626 - Naval Strike and Air Warfare Center, Naval Air Station Fallon, Nevada.[98]

- 159631 - San Diego Aerospace Museum, San Diego, California.[99]

- 159829 - Wings Over the Rockies Air and Space Museum, former Lowry AFB, Denver, Colorado. From VF-211, later used for aircraft maintenance training by Naval Air Reserve Center Denver at Buckley AFB.[100]

- 159830 - Western Museum of Flight, Hawthorne, California.[101]

- 159848 - Tillamook Air Museum, Tillamook, Oregon.[102]

- 159853 - Defense Supply Center Richmond, Richmond, Virginia.[103]

- 159856 - Naval Air Facility El Centro, California.[104]

- 160382 - Museum of Flight, Tukwila, Washington. VF-84 "Jolly Rogers" AJ202. Stationed on the USS Nimitz. This aircraft, as well as several other F-14As from the famous "Jolly Rogers" squadron, appear in the 1980 film The Final Countdown which was filmed on board the USS Nimitz. On loan from the National Museum of Naval Aviation at Pensacola, Florida.[105]

- 160386 - Naval Air Station Joint Reserve Base Willow Grove, Pennsylvania.[106]

- 160391 - Texas Air Museum, Lubbock, Texas.[107]

- 160395 - Air Zoo, Kalamazoo, Michigan.[108]

- 160401 - Fleet Area Control and Surveillance Facility Virginia Capes (FACSFAC VACAPES), Naval Air Station Oceana, Virginia.[109]

- 160403 - American Airpower Heritage Museum, Midland, Texas.[110]

- 160411 - Empire State Aerosciences Museum, Glenville, New York.[111]

- 160658 - NAES Lakehurst, New Jersey.[112]

- 160661 - U.S. Space and Rocket Center's Aviation Challenge facility in Huntsville, Alabama.[113]

- 160666 - Western Aerospace Museum, Oakland, California. Originally delivered to VF-111 in 1978, subsequently reassigned to NAVAIR test duties, permanently modified for development of follow-on avionics and weapons systems.[114]

- 160684 - Pima Air and Space Museum, adjacent to Davis-Monthan AFB, Tucson, Arizona. Repainted in its original markings as "NL 211" of VF-111 aboard USS KITTY HAWK (CV-63), as this particular aircraft appeared in its initial operational squadron service, circa 1978-1981.[115]

- 160694 - USS Lexington Museum, Corpus Christi, Texas. - Painted with Hi-Vis markings of VF-103 "Jolly Rogers". Aircraft is on loan from the National Museum of Naval Aviation at NAS Pensacola, Florida.[116]

- 160889 - Pacific Coast Air Museum at Charles M. Schulz Sonoma County Airport, Santa Rosa, California.[117]

- 160898 - Palm Springs Air Museum, Palm Springs, California.[118]

- 160902 - Riverhead, New York.[119]

- 160903 - Mid-America Air Museum, Liberal Mid-America Regional Airport, Liberal, Kansas.[120]

- 160909 - Dobbins Air Reserve Base, Atlanta, Georgia.[121]

- 160914 - Willmar Municipal Airport, Wilmar, Minnesota[122]

- 161134 - Valiant Air Command Warbird Museum, Space Coast Regional Airport, Titusville, Florida.[123]

- 161163 - Prairie Aviation Museum, Bloomington, Illinois. Depot Level Conversion performed September 1991. Retired as MODEX 205 of Fighter Squadron 213 (VF-213), Black Lions.[124]

- 162591 - Quonset Air Museum, Quonset State Airport (former Naval Air Station Quonset Point), North Kingstown, Rhode Island.[125]

- 162592 - Ronald Reagan Presidential Foundation and Library (Painted Buno 160403).

- 162608 - Southern Museum of Flight, Birmingham, Alabama.[126]

- 162689 - USS Hornet (CV-12), USS Hornet Museum, former Naval Air Station Alameda, Alameda, California.[127]

- 162694 - MAPS Air Museum, North Canton, Ohio.[128]

- 162710 - National Naval Aviation Museum, Naval Air Station Pensacola, Florida.[129]

- F-14B

- 157986 - USS Intrepid (CV-11), Intrepid Sea-Air-Space Museum, Manhattan, New York. 7th Tomcat built, retained as research and development airframe.[130]

- 161598 - Tulsa Air and Space Museum, Tulsa, Oklahoma. It has VF-41 "Black Aces" markings.[131]

- 161605 - Wings of Eagles Discovery Center/National Warplane Museum, Horseheads, New York.[132]

- 161615 - Combat Air Museum, Topeka, Kansas.[133]

- 161620 - Selfridge Military Air Museum, Selfridge Air National Guard Base, Mount Clemens, Michigan.[134]

- 161623 - Patuxent River Naval Air Museum, Naval Air Station Patuxent River, Lexington Park, Maryland. It is a former VX-23 flight test squadron aircraft.[135]

- 162912 - Grissom Air Museum, Grissom Air Reserve Base (former Grissom AFB), Indiana.[136]

- 162916 - Richard J. Goss Post #8896, East Berlin, Pennsylvania.[137]

- 162926 - New England Air Museum, Windsor Locks, Connecticut.[138]

- F-14D(R)

- 159600 - OV-10 Bronco Museum, Fort Worth, Texas. On loan from the National Museum of Naval Aviation, NAS Pensacola, Florida. Nicknamed "Christine", it was the longest-serving F-14 Tomcat in U.S. Navy. Remanufactured from F-14A to F-14D(R) configuration, it was originally built in 1976 and made the final combat deployment/cruise of the F-14 in 2006.[139]

- 159610 - Smithsonian National Air & Space Museum, Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center, Chantilly, Virginia. This F-14 was one of those involved in the second Gulf of Sidra incident.[140]

- 159619 - Florida Air Museum at Sun 'n Fun, Lakeland Linder Regional Airport, Lakeland, Florida.[141]

- 161159 - National Naval Aviation Museum, Naval Air Station Pensacola, Florida. Completed the last combat flight and the last combat carrier arrested landing (trap) by a U.S. Navy F-14.[84]

- 161166 - Carolinas Aviation Museum, Charlotte, North Carolina.[142]

- 162595 - Naval Test Wing Atlantic, Naval Air Station Patuxent River, Maryland.[143]

- F-14D

- 163893 - main gate, Arnold Engineering and Development Center, Arnold AFB, Tennessee.[144]

- 163897 - Aerospace Museum of California, McClellan Airfield (former McClellan AFB and current Coast Guard Air Station Sacramento), Sacramento, California.[145]

- 163902 - Hickory Aviation Museum at Charlotte Douglas International Airport, Hickory, North Carolina. VF-31 Tomcatters aircraft Modex number 107; flew the F-14 retirement ceremony with LCDR Chris Richard and LT Mike Petronis at the controls.[146]

- 163904 - Pacific Aviation Museum, Ford Island, Joint Base Pearl Harbor-Hickam, Hawaii.[147]

- 164342 - Wings Over Miami, Miami, Florida.[148]

- 164343 - Evergreen Aviation Museum, McMinnville, Oregon.[149]

- 164346 - Virginia Aviation Museum, Richmond, Virginia. On loan from National Museum of Naval Aviation, Pensacola, Florida. Last Tomcat to operationally trap aboard a U.S. Navy aircraft carrier.[150]

- 164350 - Texas Aviation Hall of Fame, Galveston, Texas.[151]

- 164601 - Castle Air Museum at former Castle AFB, Atwater, California.[152]

- 164603 - Grumman Headquarters, Bethpage, New York. Felix 101 from VF-31 is the last Tomcat to fly in U.S. Navy service. Final flight was from NAS Oceana, Virginia to the American Airpower Museum at Republic Airport Long Island, New York on 4 October 2006 were it was displayed for a year and a half before being moved to Grumman Plant 25.[153]

- 164604 - NAS Oceana Memorial Park, Naval Air Station Oceana, Virginia. Last F-14 manufactured, assigned to VX-4, later VX-9, at Naval Air Station Point Mugu, California during its operational service and used the callsign "Vandy 1".[154]

Specifications (F-14D)

Data from U.S. Navy file,[155] Spick,[34] M.A.T.S.[156]

General characteristics- Crew: 2 (Pilot and Radar Intercept Officer)

- Length: 62 ft 9 in (19.1 m)

- Wingspan:

- Spread: 64 ft (19.55 m)

- Swept: 38 ft (11.58 m)

- Height: 16 ft (4.88 m)

- Wing area: 565 ft² (54.5 m²)

- Airfoil: NACA 64A209.65 mod root, 64A208.91 mod tip

- Empty weight: 43,735 lb (19,838 kg)

- Loaded weight: 61,000 lb (27,700 kg)

- Max. takeoff weight: 74,350 lb (33,720 kg)

- Powerplant: 2 × General Electric F110-GE-400 afterburning turbofans

- Dry thrust: 13,810 lbf (61.4 kN) each

- Thrust with afterburner: 27,800 lbf (123.7 kN) each

- Maximum fuel capacity: 16,200 lb internal; 20,000 lb with 2x 267 gallon external tanks[34]

- Maximum speed: Mach 2.34 (1,544 mph, 2,485 km/h) at high altitude

- Combat radius: 500 nmi (575 mi, 926 km)

- Ferry range: 1,600 nmi (1,840 mi, 2,960 km)

- Service ceiling: 50,000+ ft (15,200 m)

- Rate of climb: >45,000 ft/min (229 m/s)

- Wing loading: 113.4 lb/ft² (553.9 kg/m²)

- Thrust/weight: 0.92

- Guns: 1× 20 mm (0.787 in) M61A1 Vulcan 6-barreled Gatling cannon, with 675 rounds

- Hardpoints: 10 total: 6× under-fuselage, 2× under nacelles and 2× on wing gloves[157][N 2] with a capacity of 14,500 lb (6,600 kg) of ordnance and fuel tanks[158]

- Missiles:

- Air-to-air missiles: AIM-54 Phoenix, AIM-7 Sparrow, AIM-9 Sidewinder

- Loading configurations:

- 2× AIM-9 + 6× AIM-54 (Rarely used due to weight stress on airframe)

- 2× AIM-9 + 2× AIM-54 + 3× AIM-7 (Most common load during Cold War era)

- 2× AIM-9 + 4× AIM-54 + 2× AIM-7

- 2× AIM-9 + 6× AIM-7

- 4× AIM-9 + 4× AIM-54

- 4× AIM-9 + 4× AIM-7

- Bombs:

- JDAM precision-guided munition (PGMs)

- Paveway series of laser-guided bombs

- Mk 80 series of unguided iron bombs

- Mk 20 Rockeye II

- Others:

- Tactical Airborne Reconnaissance Pod System (TARPS)

- LANTIRN targeting pod

- 2× 267 US gal (1,010 l; 222 imp gal) drop tanks for extended range/loitering time

- Hughes AN/APG-71 radar

- AN/ASN-130 INS, IRST, TCS

- Remotely Operated Video Enhanced Receiver (ROVER) upgrade

Tomcat logo

Notable appearances in media

Main article: F-14 Tomcat in fiction

See also

| United States Navy portal | |

| Aviation portal |

- 4th generation jet fighter

- Teen Series

- Grumman XF10F Jaguar

- Related development

- General Dynamics/Grumman F-111B

- Aircraft of comparable role, configuration and era

- Boeing F/A-18E/F Super Hornet

- McDonnell Douglas F-15 Eagle

- Mikoyan MiG-25

- Panavia Tornado ADV

- Sukhoi Su-33

- Related lists

- Iranian aerial victories during the Iran-Iraq war

- List of military aircraft of the United States

- List of fighter aircraft

References

Notes

- Note: Admiral Thomas F. Connolly wrote the chapter, "The TFX – One Fighter For All".[8]

- The hardpoints between nacelles include two on centerline plus four others next to nacelles. Points between nacelles can only carry a maximum of four missiles at one time. Each wing glove can carry one large pylon for larger missiles, with one rail on the outboard side of the pylon for a Sidewinder.

Citations

- "F-14 Tomcat fighter fact file." United States Navy, 5 July 2003. Retrieved: 20 January 2007.

- "Navy's 'Top Gun' Tomcat Fighter Jet Makes Ceremonial Final Flight." Associated Press, 22 September 2006. Retrieved: 17 July 2008.

- Thomason 1998, pp. 3–5.

- Dwyer, Larry. "The McDonnell F-4 Phantom II." aviation-history.com, 31 March 2010. Retrieved: 24 March 2012.

- Spick 2000, pp. 71–72.

- Marrett 2006, p. 18.

- Spangenberg, George. "Spangenberg Fighter Study Dilemma." georgespangenberg.com. Retrieved: 24 March 2012.

- Woolridge, Capt. E.T., ed. Into the Jet Age: Conflict and Change in Naval Aviation 1945-1975, an Oral History. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press, 1995. ISBN 1-55750-932-8.

- Spick 1985, pp. 9–10.

- Spick 2000, p. 74.

- Spick 2000, p. 112.

- Gunston and Spick 1983, p. 112.

- Jenkins, Dennis R. F/A-18 Hornet: A Navy Success Story. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2000. ISBN 0-07-134696-1.

- Spick 2000, pp. 110–111.

- Baugher, Joe. "Grumman F-14A Tomcat." Joe Baugher's Encyclopedia of American Military Aircraft, 13 February 2000. Retrieved: 6 May 2010.

- Donald, David. "Northrop Grumman F-14 Tomcat, U.S. Navy today". Warplanes of the Fleet. London: AIRtime Publishing Inc, 2004. ISBN 1-880588-81-1.

- [1] Space Dynamics Laboratory: Tactical Air-borne Reconnaissance Pod System – Completely Digital. Retrieved: 22 April 2012.

- Anft, Torsent. "F-14 Bureau Numbers." Home of M.A.T.S. Retrieved: 30 September 2006.

- Friedman, Norman. "F-14." The Naval Institute Guide to World Naval Weapon Systems, Fifth edition. Annapolis MD: Naval Institute Press, 2006. ISBN 1-55750-262-5.

- "F-14 upgrades." global security.org. Retrieved: 24 March 2012.

- Gobel, Greg. "Bombcat / Tomcat In Service 1992:2005". Vectorsite.net, 1 November 2006. Retrieved: 8 December 2009.

- Pike, John. “F-14 Tomcat Systems.” GlobalSecurity.org. Retrieved: 19 December 2010.

- "Approved Navy Training System Plan for the F-14A, F-14B, and F-14D Aircraft (N88-NTSP-A-50-8511B/A)". globalsecurity.org

- [2] The U.S. Navy – Fact File: F-14 Tomcat fighter. Retrieved: 22 April 2012.

- "U.S. Navy's F-14D Tomcats Gain JDAM Capability." Navy Newsstand (United States Navy), 21 March 2003. Retrieved: 20 January 2007.

- "ROVER System Revolutionizes F-14's Ground Support Capability." Navy Newsstand (United States Navy), 14 December 2005. Retrieved: 20 January 2007.

- Spangenberg, George. “Brief History and Background of the F-14, 1955-1970.” George Spangenberg Oral History. Retrieved: 23 December 2009.

- Spangenberg, George.“Exhibit VF-2.” George Spangenberg Oral History, 8 February 1965. Retrieved: 23 December 2009.

- Spangenberg, George. “Statement of Mr. G.A. Spangenberg before the Senate Armed Services Subcommittee, June 1973.” George Spangenberg Oral History. Retrieved: 23 December 2009.

- Pike, John. “F-14 Tomcat Design.” GlobalSecurity.org. Retrieved: 5 April 2012.

- Dorr 1991, p. 50.

- "F-14A, Aircraft No. 3, BuNo. 157982." F-14 Association. Retrieved: 8 December 2009.

- Sgarlato 1988, pp. 40–46.

- Spick 2000, p. 81.

- Laurence K. Loftin, Jr. "Part II: The Jet Age, Chapter 10: Technology of the Jet Airplane, Turbojet and Turbofan Systems." Quest for Performance: The Evolution of Modern Aircraft, 29 February 2009. Retrieved: 29 January 2009.

- "NAVEDTRA No: 14313, Aviation Ordanceman." globalsecurity.org. Retrieved: 8 April 2011.

- Dorr 1991, p. 51.

- Holt, Ray M. "The F-14A “Tom Cat” Microprocessor." firstmicroprocessor.com, 23 February 2009. Retrieved: 8 December 2009.

- "Interoperability: A Continuing Challenge in Coalition Air Operations." RAND Monograph Report. pp. 108, 111. Retrieved: 16 November 2010.

- “AN/ALR-67(V)3 Advanced Special Receiver.” Federation of American Scientists. Retrieved: 29 December 2009.

- Rausa, Zeno. Vinson/CVW-11 "Vinson/CVW-11 report." Wings of Gold, Summer 1999. Retrieved: 8 December 2009.

- Holmes 2005, pp. 16, 17.

- "Briefing." DoD News, 5 January 1999. Retrieved: 8 December 2009.

- Baugher, Joe. "TARPS Pod for F-14." F-14 Tomcat, 13 February 2000. Retrieved: 6 May 2010.

- Gillcrest 1994, p. 168.

- "Capt. Dale "Snort" Snodgrass, USN (Ret.) Interview by John Sponauer". (30 August 2000). SimHQ. Retrieved: 26 November 2010.

- Baugher, Joe. "F-14." U.S. Navy and U.S. Marine Corps BuNos, 30 September 2006. Retrieved: 6 May 2010.

- Donald 2004, pp. 13, 15.

- "Squadron Homecoming Marks End of Era for Tomcats". U.S. Navy, 10 March 2006. Retrieved: 20 January 2007.

- Murphy, Stephen. "TR Traps Last Tomcat from Combat Mission." Navy Newsstand, 15 February 2006. Retrieved: 20 January 2007.

- "Final launch of the F-14 Tomcat." navy.mil. Retrieved: 8 December 2009.

- Tiernan, Bill. "F-14's Final Flight." Virginian-Pilot, 23 September 2006.

- Vanden Brook, Tom. "Navy retires F-14, the Coolest of Cold Warriors". USA Today, 22 September 2006. Retrieved: 20 January 2007.

- "Pentagon shreds F-14s to keep parts from enemies." AP, 2 July 2007. Retrieved: 8 December 2009.

- "Last of the Navy’s F-14 Tomcats head for shredder; 11 remain in desert storage". USAF 309 AMARG 3 (6): 2. 7 August 2009. Retrieved 22 July 2014.

- Cooper, Tom. Persian Cats: How Iranian air crews, cut off from U.S. technical support, used the F-14 against Iraqi attackers." Air & Space magazine, November 2006. Retrieved: 24 March 2012.

- Cooper, Tom and Farzad Bishop. Iranian F-14 Tomcat Units in Combat, pp. 85–88. Oxford: Osprey Publishing, 2004. ISBN 1 84176 787 5.

- "F-14 Tomcat interceptors in Iran". Ivanov, Grigoriy, 2003

- Cooper, Tom and Liam Devlin. "Iranian Air Power Combat Aircraft". Combat Aircraft, Vol. 9 No. 6, January 2009.

- "World Military Aircraft Inventory". 2013 Aerospace Source Book, Aviation Week and Space Technology, 2013.

- "US halts sale of F-14 jet parts." BBC News. Retrieved: 8 December 2009.

- "Iranian Air Force seeks return of F-14 bombers from U.S." Tehran Times

- Parsons, Gary. "Iran wants its F-14 back." AirForces Monthly, 5 August 2010.

- "Iranian Air Force Equips F-14 Fighter Jets with Hi-Tech Radars." FARS News Agency, Iran, 5 January 2011. Retrieved: 9 September 2012.

- "Iranian F-14 fighter jet crashes in country's south, both pilot and co-pilot killed." Washington Post, 26 January 2012. Retrieved: 24 March 2012.

- "F-14 Bureau Numbers." anft.net. Retrieved: 8 December 2009.

- Anft, Torsten. "Grumman Memorial Park." Home of M.A.T.S. Retrieved: 28 December 2006.

- Anft, Torsent. "F-14 Crashes sorted by Date." Home of M.A.T.S. Retrieved: 1 January 2008.

- Spick 2000, pp. 75–79.

- "F-14 Tomcat variants". GlobalSecurity.org. Retrieved: 20 September 2006.

- "Developing F-15C." Lockheed Martin Press Release, 28 April 2010.

- Jenkins 1997, p. 30.

- Saul, Stephanie. "Cheney Aims Barrage at F-14D Calls keeping jet a jobs program." Newsday Washington Bureau, 24 August 1989, p. 6.

- Spick 2000, p. 75.

- Isham, Marty. U.S. Air Force Interceptors: A Military Photo Logbook 1946-1979. North Branch, Minnesota: Specialty Press Publications, 2010. ISBN 1-58007-150-3.

- Donald 2004, pp. 9–11.

- "F-14 History." anft.net. Retrieved: 16 November 2010.

- Taghvaee, Babak. Aviation News Monthly, UK: Key Publishing, March 2012.

- Navy's Newest Squadron Prepares for New F-35 Fighters. Navy.mil. Retrieved on 2013-08-16.

- "VF-1285." anft.net. Retrieved: 8 December 2009.

- "VF-1485." anft.net. Retrieved: 8 December 2009.

- "VF-1486." anft.net. Retrieved: 8 December 2009.

- "F-14 Tomcat/157982." Cradle of Aviation Museum. Retrieved: 27 March 2013.

- "F-14 Tomcat/157984." National Naval Aviation Museum. Retrieved: 27 March 2013.

- "F-14 Tomcat/157988." Warbird Registry. Retrieved: 27 March 2013.

- "F-14 Tomcat/157990." March Field Air Museum. Retrieved: 27 March 2013.

- "F-14 Tomcat/158623." Warbird Registry. Retrieved: 27 March 2013.

- "F-14 Tomcat/158978." USS Midway Museum. Retrieved: 27 March 2013.